Mobile Apps for Aboriginal Languages

My introduction to Darwin was on a borrowed bike used to discover the streets around CDU and eventually making my way to the city and Midil Beach markets for a Sunday evening feast of Gado-Gado watching the sunset on the sand. I’m in Darwin for a workshop organised by Steven Bird aiming to build mobile apps aimed at “Keeping our Languages Strong”. While a lot of the work with Australian languages is aimed at preservation and documentation, Steven’s work is aimed more at maintaining the living languages within their communities.

The invitees to the workshop were a mixture of technologists like me, linguists, people working with the language communities and members of the communities themselves. The premise was to bring us together to imagine what mobile apps we might build in the context of Aboriginal languages and them maybe even try to build some demonstrations as a proof of concept in the week. The first two days explored possibilities; the next two left the hackers alone to try to build something; the final morning was a show and tell and reflection on what we’d managed to achieve.

My agenda coming to the workshop was to promote the use of the Alveo Virtual Laboratory as a repository for language data. I’ve never worked with Aboriginal languages and my main contact with them is through linguists who collected data for later study; Alveo provides a repository and we are keen to be able to help look after any collections of data that would benefit from the resources we provide. So I was looking for opportunities to help collect data and provide a gateway to storing it in a repository like Alveo for later study by linguists.

On Friday morning I realised that when we frame the task as one of language maintenance rather than preservation the problems deserve a different treatment. Understand that this language isn’t something to be collected and shared back with the community but something that belongs to them that they might share with us. Helping them build an eco-system of tools that might help keep their language alive is the first priority with documentation and preservation as side effects.

Exploring Ideas

Our first session as a group was aimed at exploring possibilities. What does a language app look like, what could be done, what might be popular in the community. Our group talked about an idea that had already had some thought put into it — a “Calling to Country” app that could play a welcome message in the local language when a visitor arrived in an area. Coupled with some knowledge of local significant sites this might provide an introduction to the local culture for tourists and visitors to an area.

We wondered if it might be possible to link in to Google Now and make a Card appear when you arrived in a place showing the welcome to country and linking to the content in the app. Based on some research this seems to be an option that is limited to a small number of installed apps at present but that might be opened up in future.

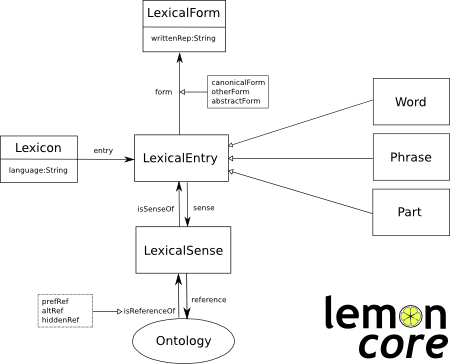

I talked about some ideas I’d had around dictionaries, how the relatedness of words might be captured and represented in some way, about the collective knowledge captured in Wikipedia and Wiktionary and how we might encourage people to collect this knowledge for Aboriginal languages. I have been wanting to apply semantic web technology to representing Aboriginal language dictionaries, in particular the Lemon model that is designed to link lexical entries and senses to ontologies like dbpedia. I think there is scope to link many language dictionaries together like this if they share common concepts. My description of these kinds of resource triggered some discussion about building an encyclopaedia linked to place that might capture stories and knowledge associated with different places such that someone might be able to find relevant entries based on where they are.

Networks for Counselling

Another surprising (to me) link was made by one member of the group who pulled out a collection of laminated work-sheets she had made to support her work in counselling. They showed different ‘prompt’ words arranged as a network (graph) showing how they might be related to each other; the size of each word was related to how likely it was to be relevant to a particular age group. The diagrams were effectively a semantic network of terms that could be used as a prompt when discussing issues in a counselling session. We talked about how we might build an app based around this idea, one that might be able to construct a suitable diagram based on information gathered from the patient. This then developed into a discussion of exploring self-help materials through this kind of interface so that this resource might be used by the community directly. All of these were great ideas but were not quite the language applications that we had been asked to come up with, so we shelved these ideas for future reference.

Community Search Engine

Our discussion of networks and wikipedia led us to thinking about finding information in documents written in Aboriginal languages and the idea of a dedicated search engine for a collection of community documents. We envisaged a kind of repository where community members could lodge documents, perhaps tagged with place and topic tags, and these could then be made available via a search or browse interface to members of the community. We imagined developing this into a place-based encyclopaedia of community knowledge, managed by the community with an interface on mobile devices to make it accessible. We thought that it could be made available in some kind of offline peer-to-peer mode in communities to make up for a lack of network access.

This was the idea that we finished the day with; we developed some scenarios and thought about where the documents might originate, who might submit them and about a process of approval by the elders in a community before documents were published widely.

I think that this project would be relatively easy to implement at a technical level. We could implement a Solr index over a document collection and build some infrastructure to allow tagging of documents with locations and other category tags. The main problem with it is who is going to take responsibility for running the servers and keeping the service alive? Perhaps this is the problem with all of the apps that we’re proposing but it seemed to be a particular issue in this case.

Pictures and Words

Day two saw us re-convening around four apps that we had proposed the previous day. Our document search app was one of these but following some overnight thought and more discussion we decided that it was ‘too hard’. The context of this workshop was to be able to build something and to focus on mobile applications; the document repository ideas was mainly a backend service, the mobile part was just reading documents and so was perhaps not that interesting.

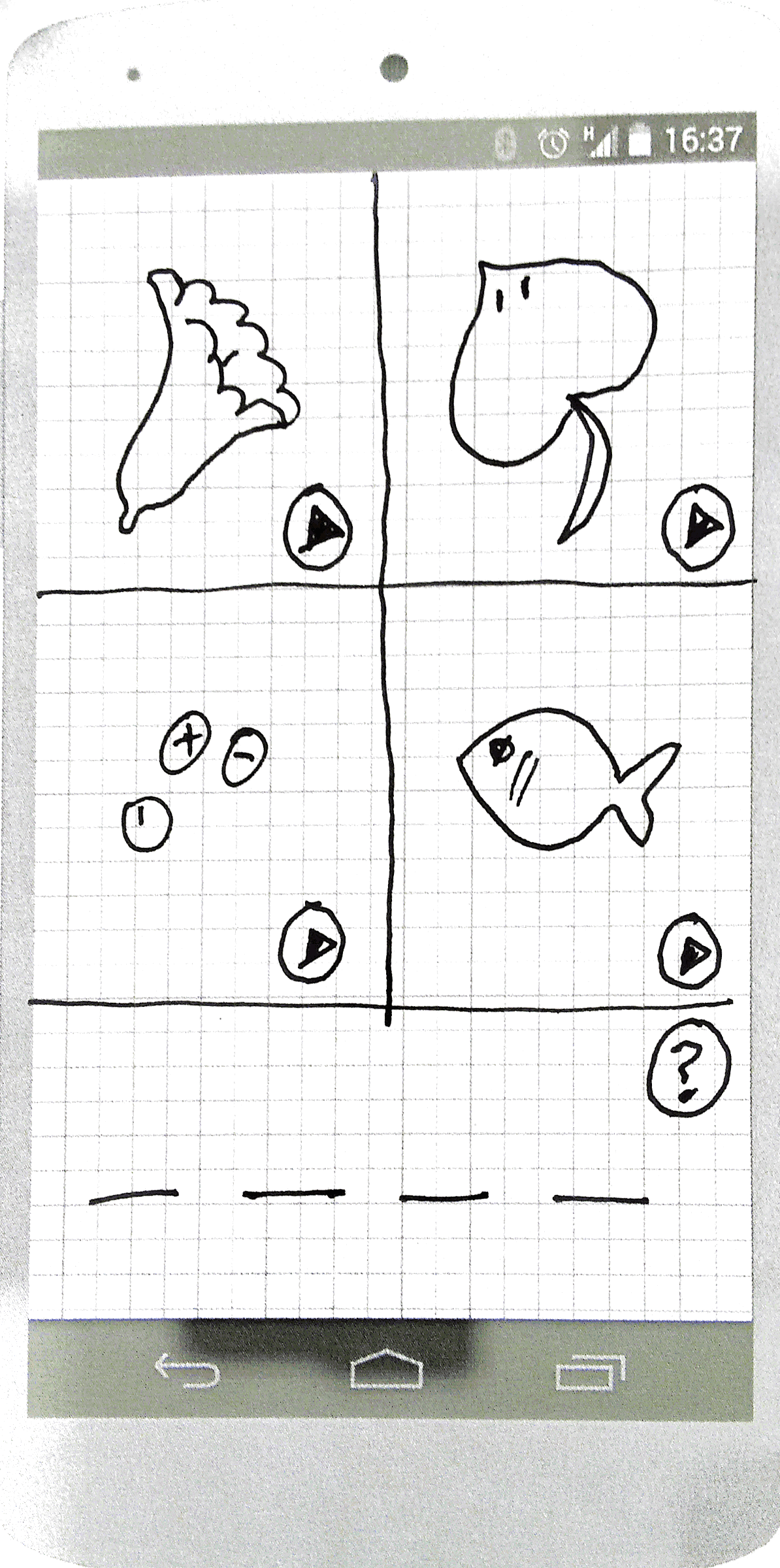

We re-focussed and talked over some of the other things that had come up the day before. We were still interested in networks and links between words and concepts and one idea that was mentioned was a mobile game that is apparently very popular in the communities already. Four Pictures One Word is a puzzle game that shows four pictures and asks the user to guess the one word that is common to them all. The game is played in English and is a free download - money changes hands when you can’t get the answer and want to buy a clue. Many of us in the group had never heard of this game but it is apparently hugely popular.

The attraction of this game was that it links together words into some kind of semantic category. We imagined a version in an Aboriginal language that would show pictures, perhaps with an associated spoken prompt, and ask for a response in the language. Our version of the game would have an interface to allow new games to be constructed and shared with others. In this way we allow the community to support the game in their own language and build resources over time. The collection of images and recordings would grow and could be used in many games. The obvious side effect is a collection of recordings of words in the language along with some semantic relations - even if those relations are not well defined.

We developed this idea in to a full proposal and thought about how different users would work through the gameplay and game construction. The game itself is relatively straightforward and there is an existing game to copy from so most of the thinking went into how new games would be made and the infrastructure we would need to store words and games on the back-end.

Part of the motivation for this game was the collection of language data for possible future linguistic analysis. To facilitate this we need to collect as much useful metadata as possible about the speaker their location and the word or phrase being spoken. Balanced with this is the need to not collect data that might be considered private or to complicate the game creation process too much.

We presented our idea back to the larger group and got some great feedback. Our presentation included some sample games put together by the native speakers in our group. I was surprised at how well these worked in the presentation and the enthusiasm they generated; it seems that this really is an idea that might work in the community, at least from a game-play perspective.

Building

For the next couple of days the developers got together to explore the implementation of the ideas that had been generated. From our perspective, there were some common themes among the ideas that might be able to use common components in their implementation. From my point of view the most interesting of these was the need to store recordings of words and phrases for use in the games. There is a clear analog here to the capabilities of the Alveo system but importantly, the data that backs up these games is not a curated collection that can be shared with researchers - it is raw data collected by the language community that might one day be shared.

The data for our game can be structured very much like a dictionary with entries for lexical items that have associated textual transcriptions, images and sound recordings. A naive implementation would just lump these together in a single record but we can apply our understanding of lexical structure to develop a more sophisticated store. I look to the Lemon

Ontology for a useful lexical model, it might represent:

- each word as a LexicalEntry

- the pronunciation of the word as a kind of LexicalForm

- a definition or image associated with the word as attached to a LexicalSense

An advantage of this form would be the ability to support multiple languages referencing `meanings’ represented by images. It might also be possible to link to other ontologies to describe meanings, for example to dbpedia if there are relevant entities described there.

For the purposes of our hackathon session however, we compromised and explored a simpler storage model using Google’s Firebase cloud storage solution. Firebase is a JSON data store particularly useful for developing mobile applications. I hadn’t used it before so it was interesting to learn about this new technology. In Firebase you essentially store one large JSON object structure; the mobile app can then request that all or part of that is available locally and local changes are reflected instantly on the device. For this project we hacked together a data store that is reminiscent of the Alveo data model: each word is an item and can have associated documents that are the audio recording or depiction (image) associated with the word. Metadata on the items records the language, speaker details etc. This is more of an archive of recordings than a lexical structure but it serves the purpose of representing the resources for the game we are developing.

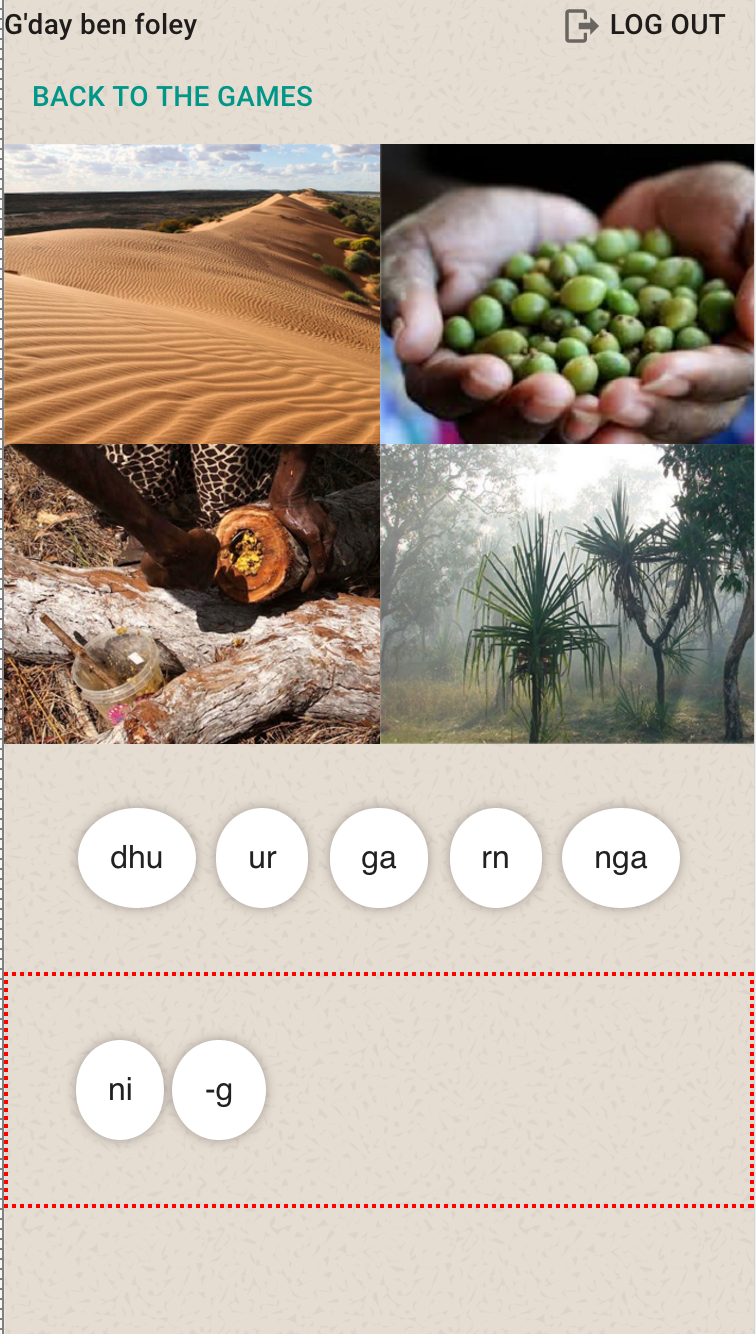

Ben Foley worked on the front end game implementation using the AngularJS framework. With the help of some boilerplate put together by Matt Bettinson he was able to generate a working version of the game while learning about Angular at the same time. The screenshot here shows a sample game in progress. We were able to demonstrate this at the final presentations and got great feedback from the group who were pleased to see their idea at least partially implemented in a real application.

The Next Steps

I think the workshop showed that there is a lot of scope for applications that deal with language data in a way that can support the language community rather than just treat them as a source of research materials. All of the ideas we generated were applications that would collect data and use it in a useful context: to inform, to entertain or to engage.

Between the different projects that we proposed there was a clear common need for a back-end store of data that was a hybrid of a lexicon and a repository of recordings and images. Alveo provides this kind of service but it isn’t appropriate to have these game-creation engines upload data directly to Alveo: our system is owned by researchers and keeps data as a resource for researchers - the need here is for a data store owned by the community and managed for or by them for the purpose of language maintenance. There should of course be a gateway from the community resources to allow for future research use of this data if it is deemed appropriate; but such usage should not be the primary goal of the data store.

While it would be possible to use the kind of custom data store that we hacked together for our game to support one or even a few different applications, it makes more sense to think about the design of a data store more generally to support as wide a range of applications as possible. The kind of data store hinted to above would model the lexical resources and recordings appropriately and could then be the basis of a wide range of use cases. We contrasted this approach with the common model that has been used in the past for building applications around Aboriginal languages. In many cases a group is funded to build an app, contracts to a development group who use whatever technology they understand to store the data in a custom database. The disadvantage is that any data stored in this way is locked away and will not be available for other kinds of use. The goal of the kind of back-end that it could become a resource for future use and if we explicitly build in a more general interface - new ideas could flow from seeing the data in-place as it grows.

My thanks to Steven Bird for the invitation to Darwin and to the CoEDL for the funding. It was an amazing experience and I hope we can build on it to progress some of these ideas in the future.